The tragic suicide of Kosta Karageorge once again forces a discussion of how head injuries are affecting athletes

by Shimbo

How many more?

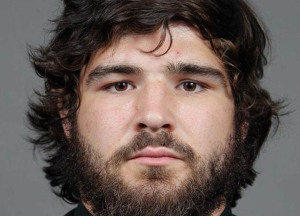

In the wake of finding Ohio State defensive tackle Kosta Karageorge dead of what looks to be a self-inflicted gunshot wound on Sunday morning, the first question asked about a tragedy such as this is not whether he had personal problems that led to his fate, but whether sport served as a catalyst.

Much will be said in the next few days and weeks about whether the 22-year-old Karageorge, who complained of “headaches and confusion” in the wake of a number of sustained concussions, was yet another victim of the pervasive effects of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a “progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in athletes (and others) with a history of repetitive brain trauma, including symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic subconcussive hits to the head.”

One of Karageorge’s last text messages to his mother said, “I am sorry if I am an embarrassment but these concussions have my head all fucked up.”

What we know about CTE to date is probably not nearly as much as we need to know, however we do know that CTE is believed to affect boxers since the early 20th century. But as more and more data becomes available through the names added to the growing list of NFL players who suffered from the disease we are getting a much grimmer picture of the situation.

Until recently, CTE was primarily undetectable until after death, but the sheer number of cases involving the suicides of high-profile former players such as Junior Seau, Jovan Belcher and Dave Duerson, coupled with the increasing number of still-living former and now current players who report symptoms such as memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, and in most cases progressive dementia shed a new light on the neurological disorder.

But it’s not just about football.

Now we have no idea whether or not Karageorge had CTE, and it’s important to note that he’d only been with the Ohio State football program since August, according to head coach Urban Meyer. Before joining the football team as a walk-on, Karageorge’s passion was wrestling.

But that may not matter.

According to a 2010 article in the Journal of Forensic Nursing, CTE was found in a former professional wrestler who also committed suicide after murdering his wife and son.

That wrestler was Chris Benoit.

The one thing all of these athletes have in common? Repeated concussions. according to statistics provided by Headcase Company, a supplier of protective sports equipment, roughly 3.8 million concussions were reported in 2012 alone. Here are a few other disturbing statistics:

- 33 percent of all sports concussions happen at practice

- 39 percent — the amount by which cumulative concussions are shown to increase catastrophic head injury leading to permanent neurologic disability

- 47 percent of all reported sports concussions occur during high school football

- 1 in 5 high school athletes will sustain a sports concussion during the season

- 33 percent of high school athletes who have a sports concussion report two or more in the same year

- 4 to 5 million concussions occur annually, with rising numbers among middle school athletes

- 90 percent of most diagnosed concussions do not involve a loss of consciousness

- An estimated 5.3 million Americans live with a traumatic brain injury-related disability (CDC)

The facts are clear: while concussions are common and likely unavoidable, something must be done to change the way sports are played at all levels. The bitter irony here is that not so long ago, it was common to celebrate big hits, whether it was a linebacker crushing a running back or wide receiver with a punishing hit or a big body slam from a burly wrestler, having one’s bell rung was a badge of honor both on the giving and receiving end.

Now we know better.

If we are going to enjoy our favorite sports for years to come, there has to be a sustainable, progressive change that helps our athletes not only continue to play safely, but also have a quality of life that lasts into their retirement years, which in the case of football, can begin as early as the mid-to-late 20’s.

Whether it was the suicides or the increased media coverage, professional sport seems to finally be taking the research behind CTE more seriously. Boston University’s CTE Center, with support from the NFL Player’s Association, is in the process of conducting a pair of clinical studies, known as LEGEND and DETECT, with the goal of better detecting the disorder while current and former players are still alive. This is in addition to BU’s Brain Bank and donation registry, where players can donate their brains for research purposes.

While these advances on the medical end are promising, the old adage “an ounce of prevention is worth an pound of cure” has never been more relevant. While the discussion of CTE is usually focused on retired players, we can no longer ignore that these symptoms are appearing in younger athletes. If the tragic death of Kosta Karageorge is to have any meaning, it’s that we must be more vigilant about head injury in sports.

Just using football as an example, it’s become clear that the speed and size of the current game has hit the limits that a human can withstand. According to the NFL Players Association the average career length is about three years. The NFL claims that the average career is about six years (for players who make a club’s opening day roster in their rookie season). This can be attributed to the sheer amount of injury that’s visited on a player during their professional career, but it also points to the punishment they endure as early as high school.

Without real change, especially in the realm of brain injuries, the average career length will only get shorter.

There is currently no cure for CTE, and given the nature of traumatic brain injury, there may never be one. That said, we have to look at what we can do to limit and decrease the number of sustained concussions, particularly in youth sports. We have to get past the notion of “looking soft” or “killing the game”, because as it is, the game is killing a number of athletes slowly, and in time, we may not have the luxury of the sports we love.

Hashim R. Hathaway (Uncle Shimbo) is the host of the Never Daunted Radio Network, and proud father to NeverDaunted.Net. You can reach him on Twitter @NeverDauntedNet